An EFF Investigation Finds NIST/FBI Experimented with Religious Tattoos, Exploited Prisoners, and Handed Private Data to Third Parties Without Thorough Oversight

Tattoos are inked on our skin, but they often hold much deeper meaning. They may reveal who we are, our passions, ideologies, religious beliefs, and even our social relationships.

That’s exactly why law enforcement wants to crack the symbolism of our tattoos using automated computer algorithms, an effort that threatens our civil liberties.

Right now, government scientists are working with the FBI to develop tattoo recognition technology that police can use to learn as much as possible about people through their tattoos. But an EFF investigation has found that these experiments exploit inmates, with little regard for the research’s implications for privacy, free expression, religious freedom, and the right to associate. And so far, researchers have avoided ethical oversight while doing it.

The research program is so fraught with problems that EFF believes the only solution tis for the government to suspend the project immediately. At a minimum, scientists must stop using any tattoo images obtained coercively from prison and jail inmates and tattoos that contain personal information or religious or political symbolism.

EFF has been filing public records requests around the country to reveal how law enforcement agencies are using mobile biometric technology—including facial recognition, digital fingerprinting, and iris scanning—to identify people based on their physical and behavioral characteristics. As part of this investigation, we learned that the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST), one of the oldest federal scientific institutions, began an initiative in 2014 to promote and refine automated tattoo recognition technology for the FBI.

Tattoos, of course, are a biometric characteristic, but they’re also unique because they’re elective (people generally choose to get tattoos) and expressive (they say things about our personal lives). Importantly, tattoos are also speech, and any attempt to identify, profile, sort, or link people based on their ink raises significant First Amendment questions.

The FBI’s plans for automated tattoo recognition go beyond developing algorithms that can identify people by their tattoos. The experiments facilitated by NIST also focused on improving technology that can map connections between people with similarly themed tattoos or make inferences about people from their tattoos (e.g. political ideology, religious beliefs). On top of the free speech concerns, the project should raise red flags for religious liberty advocates, since many of the experiments involved sorting people and their tattoos based on Christian iconography.

NIST’s Tattoo Recognition Technology program also raises serious questions for privacy: 15,000 images of tattoos obtained from arrestees and inmates were handed over to third parties, including private companies, with little restriction on how the images may be used or shared. Many of the images reviewed by EFF contained personally identifying information, including people’s names, faces, and birth dates.

If that wasn’t alarming enough, NIST researchers also failed to follow protocol for ethical research involving humans—they only sought permission from supervisors after the first major set of experiments were completed. These same researchers have also not disclosed to their supervisors that the tattoo datasets they are using to seed the experiments came from prisoners and arrestees. Under federal research guidelines, research involving prisoners triggers enhanced scrutiny and ethical oversight to prevent their exploitation. Instead, NIST and the FBI are treating inmates as an endless supply of free data.

Now, with NIST and the FBI on the precipice of a new, larger experiment that will use upwards of 100,000 tattoo images, officials must suspend any further research into tattoo recognition technology until they address the First Amendment, ethical, and privacy concerns EFF has identified.

Updated June 6, 2016: NIST provided a written response to reporters and EFF.

Note: Because many of the tattoo images in the data set contain personal information, EFF will not be re-publishing any government records featuring the images.

Tattoos and Law Enforcement

Tattoos are free speech that we wear on our skin.

When we look at our tattoos, we may see important milestones in our lives or mistakes that we made in our youth. We may see symbols that represent our ethnic heritage or our pride in our affiliations, such as our military units, church membership, or political ideology. We get tattoos of the musicians and films that have enchanted us, or we memorialize the birth of our children and the family members who have passed away. Some may even get tattoos of our medical conditions in case of an emergency. Our tattoos express who we were, who we are, and who we hope to be.

But when law enforcement looks at our tattoos, they see unique biometric identifiers and a shortcut to learning our personal beliefs and our social connections.

Today, law enforcement generally obtains images of tattoos by photographing detainees during the jail booking process or during prison intake. However, police have been known to collect data on tattoos during routine stops, often using that information to place people in controversial gang databases. In one particularly heinous case, police in San Diego are being sued after officers entered a strip club, detained workers, forced them to pose nude and took photos of their tattoos.

Traditionally, police have used regular cameras to collect these images and kept the photos in physical albums and text-based databases. Now, law enforcement is pursuing mobile devices and apps that can collect and analyze tattoos instantly. Due to recent advances, current algorithms are able to match tattoos with greater than 90% accuracy. However, algorithms that can accurately connect people based on their tattoos are still in their nascent stages.

NIST's Official Tattoo Recognition Technology Logo

That’s where NIST comes in.

In 2014, NIST’s Image Group launched the Tattoo Recognition Technology program, with sponsorship from the FBI’s Biometric Center for Excellence, to conduct experiments to accelerate this technology in the private and academic sectors.

The first major foray was called the Tattoo Recognition Technology Challenge—Tatt-C for short. NIST and the FBI compiled an “open tattoo database” of 15,000 images—many, if not most collected from prisoners—that formed the basis of NIST’s Tatt-C competition. The data was distributed to 19 organizations—five research institutions, six universities, and eight private companies, including MorphoTrak, one of the largest marketers of biometric technology to law enforcement agencies. The dataset was designed to be the first standardized metric for testing tattoo recognition algorithms.

The Tatt-C competition required participants to perform a series of tests and report their results to NIST, which is part of the U.S. Department of Commerce. These experiments included identifying whether an image contained a tattoo and whether algorithms could match different images of the same tattoo taken over time. The most alarming research involved matching common visual elements between tattoos with operational goal of establishing connections between individuals.

This summer, NIST plans to launch the next phase: Tattoo Recognition Technology Evaluation, or Tatt-E. These experiments will be conducted internally by NIST using third-party algorithms to analyze an even larger dataset. NIST researchers are hoping to amass a dataset of more than 100,000 images for experimentation that would be collected by the Pinellas County Sheriff’s Department in Florida, the Michigan State Police, and the Tennessee Department of Corrections.

Based on the lack of attention to civil liberties, privacy, and research ethics, EFF believes that Tatt-E should not occur and that NIST’s tattoo recognition research more generally should not move forward without proper oversight.

Experimenting With Religious Tattoos

NIST was not coy about the information tattoos can reveal about a person’s personal beliefs. As researchers wrote in several of NIST’s whitepapers on tattoo recognition: “Tattoos provide valuable information on an individual’s affiliations or beliefs and can support identity verification of an individual.”

Following EFF criticism, NIST scrubbed the "religious" line from the slide

One slide from a workshop went even further. In answering the question of “Why Tattoos?” researchers said that tattoos “suggest affiliation to gangs, sub-cultures, religious or ritualistic beliefs, or political ideology” and “contain intelligence, messages, meaning and motivation.”

After EFF brought our concerns to NIST officials, the agency responded by attempting to scrub references to religion and politics from its public documentation. But officials can’t erase how the experiments targeted individuals with religious tattoos.

For example, the “tattoo similarity” and “mixed media” experiments tested how well algorithms could match different people’s tattoos that contained visually similar imagery. Many of the tattoos of the test subjects contained Catholic iconography, such as Jesus Christ’s crucifixion, praying hands with rosaries, and Jesus Christ wearing the crown of thorns.

It is totally inappropriate for researchers to use religious imagery for experiments, especially if the end result is technology that can be used to group people who share common beliefs.

While NIST researchers were enthusiastic about the ability to divine this kind of meaning from tattoos, none of the proposals or subsequent reports analyzed or even acknowledged the potential impact on civil liberties.

These experiments may not have been allowed to move forward if they had been conducted with proper oversight, which is why EFF is calling for a suspension of this research. At the very least, no further tests should be allowed that involve religious imagery or linking people based on similar tattoos.

Experimenting With Inmates as Human Subjects

NIST researchers are using tattoo images obtained from prisons and jails without questioning whether the experiments require enhanced oversight to comply with federal ethical rules regarding research on prisoners. Rather, they are treating inmates as a bottomless pool of free data.

When government scientists perform experiments involving people, they are supposed to adhere to the Common Rule, a series of federal regulations and principles for ethical research.

The Common Rule was developed in response to historically troubling scientific research on humans, such as U.S. experiments with syphilis on African-American men in the South. Its purpose is to provide independent oversight of any research conducted on humans. The rule also imposes heightened scrutiny on research involving vulnerable populations, such as prisoners. Today, the Common Rule has been adopted by more than 15 federal agencies, including NIST.

Whenever research involves prisoners, the Common Rule has a special, independent section that limits the types of experiments than can be conducted and requires rigorous oversight by an Independent Review Board (IRB). That oversight body must include at least one inmate or their representative. The goal is to protect prisoners and detainees from being coerced into becoming research subjects merely because they are incarcerated.

NIST’s first tattoo recognition experiment, Tatt-C did not go through this process in advance of conducting the research, despite the fact that the images were collected from inmates.

Documents obtained by EFF through the Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) show that project leaders didn’t even run their experiments up the ladder for ethical review until after the experiments were completed. The researchers claimed they didn’t know that was required.

A NIST Supervisor retroactively exempted research from oversight.

In their subsequent filings to supervisors, these researchers failed to disclose that the research involved prisoners. Instead, researchers only said that the information was “operationally collected.” NIST officials later retroactively approved the research after concluding that it did not involve research on human subjects, much less research on prisoners.

However, the images themselves clearly show that samples came from prisoners. Many of the images feature inmates in prison uniforms and, in some cases, handcuffs. Thus, the images were taken for law enforcement purposes, not for research, raising questions about whether prisoners were aware that their personal information would be used in this way, and whether they consented to being research subjects.

NIST further claims that the research did not require IRB review because the FBI had stripped the images of all “identifiable private information.” What NIST means is that the names of the individuals were removed and replaced with code, although other identifiers were maintained. We believe this step did not render the images free of identifiable private information.

Tattoos are inherent personally identifiable information—a tattoo is unique to the person who wears it. Otherwise, law enforcement would have no interest in using tattoos to identify subjects. Beyond that, the tattoos themselves often included sensitive, identifiable information, such as names and dates of birth of relatives.

This is further underscored by how NIST characterized the research in an article promoting the project in NIST's in-house magazine: the headline read, “Nothing Says You Like a Tattoo.”

Researchers are attempting to have it both ways. In scientific papers, NIST regularly emphasized that tattoos are valuable for identifying people, but when it came to filing disclosures, researchers contradicted themselves, saying “tattoo images are not well-suited for individual identification.” Yet, several algorithms were able to match an individual’s tattoos with more than 95% accuracy.

With the upcoming Tatt-E project, EFF is concerned that researchers will once more ignore the fact that these images are identifiable and came from prisoners. Although researchers working on Tatt-E are now asking supervisors for approval before doing any work with the tattoo images, time and time again over the last year, supervisors have declined to require IRB oversight. EFF believes that these determinations have been based on incomplete evaluations and misstatements about the nature of the images.

NIST’s failure to follow the Common Rule’s oversight requirements is not some procedural hiccup. Inmates are unable to opt out of law enforcement taking photos of their tattoos in a correctional setting. Worse, the images are now being used for an entirely different purpose and it is highly unlikely that the FBI sought informed consent before handing over the images to third parties for research. These problems underscore EFF’s concerns about scientific ethics and human rights, especially since images captured under duress were handed over to third parties, several of which are for-profit businesses that will ultimately financially benefit from access to the dataset.

The agency should act responsibly and halt the program until it goes through the full oversight process.

Research Lacking Basic Privacy Safeguards

EFF is also concerned that NIST and the FBI did not impose adequate privacy safeguard before sharing a massive tattoo database containing personal information with a number of private companies.

The documentation indicates that the Tatt-C dataset was provided to third parties with very little restrictions on who can access the images and how long the images may be retained. As a result, many of the public reports and presentations published online contain images of tattoos that should not have been made publicly available.

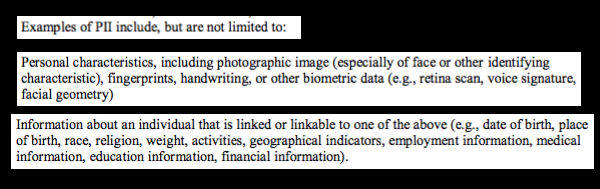

NIST’s position contradicts the agency’s own guidelines for protecting Personally Identifiable Information (PII). In 2010, the agency published a handbook on how other federal agencies can protect PII from online data breaches. In the handbook, NIST advisors stated that photographic images and biometric data are PII, especially images that reveal a person’s religion, date of birth, or “activities.”

From NIST's "Guide to Protecting the Confidentiality of Personally Identifiable Information":

EFF’s review of the images made public shows that PII was not fully removed from the files. Several of the images contained text spelling the names of family members. In at least two cases, these included the full names of the family members. In another tattoo, a 14-year-old child’s name was listed along with her date of birth.

Many of the tattoos were located on parts of the body that would not be exposed in public, with the images showing inmates lifting up their shirts, pant legs, and sleeves to reveal tattoos. The average person would be alarmed to discover that tattoos located on intimate parts of their bodies, revealing potentially personal information, were handed over to third parties and published in publicly available research papers and presentations.

Considering the Tatt-C project was conducted without adequately protecting the privacy of its research subjects, NIST must take steps to remediate any damage the experiments may have caused. NIST can start by requiring all third parties who received the datasets to return them immediately and destroy all copies. If the program is allowed to continue, researchers must take steps to ensure that tattoos that contain PII are eliminated from the dataset. Further, NIST must put in place strict protocols regarding when images can be shared publicly, such as in presentations or reports.

NIST Must Do the Right Thing

In discussions with EFF, NIST has indicated that it is looking more closely at the project, but has given no public indication that it will take any action to delay or suspend the program—except for removing questionable presentations from its website. NIST’s next, larger experiment—Tatt-E—will start this summer unless we do something about it. (Update: On June 6, 2016 NIST provided a written statement.)

Join us today in sending a message to NIST that this research is unacceptable. While law enforcement may have its sights set on our tattoos, scientists must not turn a blind eye to the ethical implications and the impact on society at large.