In April, Mexican federal police arrested Keith Raniere, taking him from the $10,000-per-week villa where he was staying and extraditing him to New York. According to the NY Daily News, Raniere, leader of self-help group NXIVM (pronounced “nexium”), is now being held without bail while he awaits trial on sex-trafficking charges. Through NXIVM, he preached “empowerment,” but critics say the group was a cult, and engaged in extreme behavior, including branding some women with an iron.

This was not the first controversial program Raniere was involved in. In 1992, Raniere ran a multilevel marketing program called “Consumer Buyline,” which was described as an “illegal pyramid,” by the Arkansas Attorney General’s office. More recently, he has collected more than two dozen patents from the U.S. Patent Office, and has more applications pending—including this one, which is for a method of determining “whether a Luciferian can be rehabilitated.”

The USPTO has granted Raniere protection for a variety of curious inventions, including a patent on “analyzing resonance,” which eliminates unwanted frequencies in anything from musical instruments to automobiles. Raniere also received a patent on a virtual currency system, which he dubbed an “entrance-exchange structure and method.” He applied for a patent on a method of “active listening,” and received patents on a system for finding a lost cell phone, and a way of preventing a motor vehicle from running out of fuel. NXIVM members reportedly identified their levels with various colored sashes, which helps explain Raniere’s design patent on a “rational inquiry sash.”

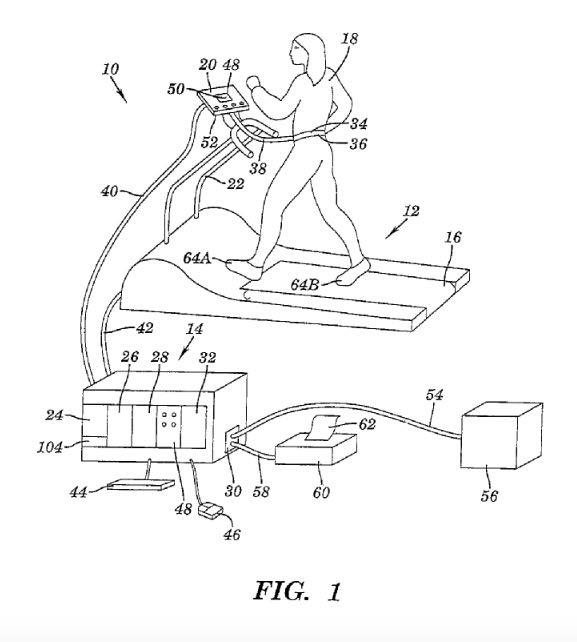

Today, we’re going to focus on Raniere’s U.S. Patent No. 9,421,447, a “method and apparatus for improving performance.” The patent simply adds trivial limitations to the basic functioning of a treadmill, like timing the user and recording certain parameters (speed, heart rate, or turnover rate.) Since most modern treadmills allow users to precisely measure performance on a variety of metrics, the patent is arguably broad enough that it could be used to sue treadmill manufacturers or sellers.

Given Raniere’s litigation history, that’s not such a remote possibility. NXIVM has sued its critics for defamation—enough that the Albany Times-Union called NIXVM a “Litigation Machine.” And Raniere sued both AT&T and Microsoft for infringement of some patents relating to video conferencing. The latter suit ended very badly for Raniere, who was ordered to pay attorneys’ fees after he couldn’t prove that he still had ownership of the patents in question. So it’s worth taking a look at how Raniere got the ‘447 patent.

Raniere’s Law ™

Raniere has never been shy about proclaiming how special he is. His bio on a website for Executive Success Programs, a series of courses run by NXIVM, explains that he could “construct full sentences and questions” by the age of one, and read by the age of two. Raniere was an East Coast Judo Champion at age 11, recruits are told, and he entered college at Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute by age 16. The honorifics continue:

He has an estimated problem-solving rarity of one in 425,000,000 with respect to the general population. He has intellectual patents pending in the areas of human potential and ethics, expression, voice and musical training, athletic performance, commerce, education and learning, information processing and human modeling. He also holds several technological patents on computer inventions and a sleep guidance system.

Raniere may be able to convince NXIVM followers that he is a one-in-425 million level genius. A new article from Vanity Fair explains that, inside NXIVM, Raniere’s patents were often used as evidence of his brilliance. But how did Raniere convince the US Patent and Trademark Office of his inventing abilities?

Ultimately, he didn’t really have to. Taking a close look at the history of Raniere’s patent application shows how the deck is stacked in favor of a determined, well-funded applicant. For someone who’s determined to prove they’re a great inventor, and is reasonably well-funded, the patent office can ultimately be cowed into compliance.

In this case, Raniere’s original patent application claimed a “performance system” with a “control system” and a sensor for monitoring “at least one parameter.” His examples went beyond exercise: he intended to patent humans making mathematical calculations at increasing speed, or a weightlifter decreasing the time between repetitions.

Appropriately, the examiner rejected all 13 of his proposed claims. But nothing stops patent applicants from coming back and trying again—and again—and that’s exactly what Raniere did. To his bare-bones description of a “performance system” he added this dose of jargon:

Wherein said control system includes a device to determine a point of efficiency, said point of efficiency occurring when the linear proportional rate of change in [] at least one parameter of the subject being trained varies rapidly outside of the state of accommodation and the range of tolerance.

Whew! That’s a lot of verbiage just to explain that the same “performance system” is measuring how fast changes occurs. The patent would be infringed by any treadmill that could measure a changing variable. Even though earlier patents had described essentially the same thing—Raniere’s lawyers insisted that his idea of measure the “rate of change” was “completely different” from a system that used a “precalculated range.”

The examiner rejected Raniere’s application again, noting that an older patent for an exercise bike attached to a video game still fulfilled all the elements of Raniere’s new, jargon-filled patent.

But Raniere simply paid $470 to file a “request for continued examination,” and kept pounding his fist on the proverbial table. Raniere, or his lawyers, bloated Claim 1 up with yet more language about the point of efficiency occurring “just prior to the subject no longer being able to accommodate additional stress” and entering a state of exhaustion, and claimed now that it was this more narrow description that was his stroke of genius.

“Nowhere in [earlier patent] Hall-Tipping is it suggested that the user be exercised to the point of exhaustion,” pointed out Raniere’s lawyers, this time around.

Rejected again, they had an interview with the examiner before coming back with yet another $470 “continued examination” request. Then Raniere loaded up Claim 1 with almost twice as much language about the system repeating itself, and re-measuring new “points of efficiency.”

This went on and on [PDF], with Raniere continuing to change language and add limitations. Eight times, the examiner threw out every single one of his claims. Finally, after he added language about the “range of tolerance” being plus or minus two percent, his claims were allowed.

In his specification, Raniere was typically un-self-effacing. He crowed that he had created “Raniere’s Maximal Efficiency Principle™” or “Raniere’s Law™.” (The guy is clearly into branding.)

Unfortunately, this is par for the course. Determined patent applicants get an endless number of chances to create a piece of intellectual property that just barely avoids all the other patents and non-patent art that overworked patent examiners are able to find. The strategy is: find a basic process, and slowly add limitations until you get a patent. That’s how we get patents on filming a yoga class and Amazon’s patent on white-background photography. The fault lies not so much with the examiner here, but with the Federal Circuit for interpreting patent law’s obviousness standard in a way that effectively prohibits the Patent Office from relying on common sense.

So what’s the solution? We need the Federal Circuit to apply the Supreme Court’s decision in KSR v Teleflex more faithfully and allow the Patent Office to use common sense when faced with mundane claims. We also need to defend the Alice v. CLS Bank ruling so that examiners can reject patents that claim abstract ideas implemented with conventional tools (like treadmills). Patent law should also be changed so that applicants don’t get an endless number of bites at the apple.