The rollout of fiber broadband will never make it to many communities in the US. That’s because large, national ISPs are currently laying fiber primarily focused on high-income users to the detriment of the rest of their users. The absence of regulators has created a situation where wealthy end users are getting fiber, but predominantly low-income users are not being transitioned off legacy infrastructure. The result being “digital redlining” of broadband, where wealthy broadband users are getting the benefits of cheaper and faster Internet access through fiber, and low-income broadband users are being left behind with more expensive slow access by that same carrier. We have seen this type of economic discrimination in the past in other venues such as housing, and it is happening now with 21st-century broadband access.

It doesn’t have to be this way. Federal, state, and local governments have a clear role in promoting anti-discrimination deployment and historically have enforced rules to prevent unjust discrimination. States and local governments have power through franchise authority to prohibit unjust discrimination through build-out requirements. In fact, it is already illegal in California to discriminate based on income status, as EFF noted in its comments to the state’s regulator. And cities that hold direct authority over ISPs can require non-discrimination like New York City just did when it required Verizon to deploy 500,000 more fiber connections last year to low-income users.

That’s why dozens of organizations have asked the incoming Biden FCC to directly confront digital redlining after the FCC reverses the Trump era deregulation of broadband providers and restore their common carriage obligations. For the last three years, the FCC had abandoned its authority to address these systemic inequalities causing it to sit out the pandemic at a time when dependence on broadband is sky-high. It is time to treat broadband as important as water and electricity and ensure that as a matter of law everyone gets the access they deserve.

What the Data Is Showing Us on Fiber in Cities

A great number of people in cities that can be served fiber in a commercially feasible manner (that is, you can build it and make a profit without government subsidies) are still on copper DSL networks. Studies of major metropolitan areas such as Oakland and Los Angeles County are showing systemic discrimination against low-income users in fiber deployment despite high population density, and because income can often serve as a proxy for race, this falls particularly hard on neighborhoods of color.

Other studies conducted by the Communications Workers of America and National Digital Inclusion Alliance have found that this digital redlining is systemic across AT&T’s footprint with only 1/3 of AT&T wireline customers connected to its fiber. In fact, not only is AT&T not deploying fiber to all of their customers over time; it is now in the process of preparing to disconnect its copper DSL customers and leaving them no other choice than an unreliable mobile connection.

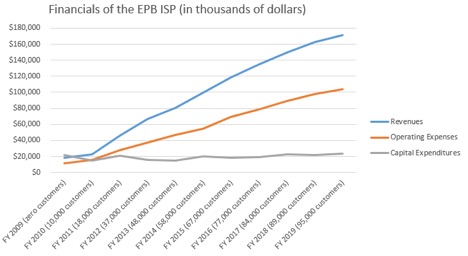

There are no good reasons for this discrimination to continue. For example, Oakland has an estimated 7000+ people per square mile, which is far above sufficient density to finance at least one city-wide fiber network. Tightly packed populations are ideal for broadband providers because they have to invest less in infrastructure to reach a large number of paying customers: 7,000 users per square mile is far more than a provider needs to pay for fiber. Chattanooga, which currently has its fiber deployed by the local government, has a population density of only 1222 people per square mile. Since the Chattanooga government ISP publicly reports its finances in great detail, we can see its extremely rosy numbers (chart below) with a fraction of the density of Oakland and many other underserved cities. In fact, rural cooperatives are doing gigabit fiber at 2.4 people per square mile.

EFF assembled this chart based on publicly reported data by EPB available at the following link (https://epb.com/about-epb/leadership-annual-reports)

In other words, there are no good reasons for this discrimination. If governments require carriers to deploy fiber in a non-discriminatory way, they will still make a profit. The question really boils down to whether we are going to allow incrementally higher profits from discrimination to continue despite historically enforcing laws against such practices.

There Are Concrete Ramifications for Broadband Affordability If We Do Not Resolve Digital Redlining of Fiber in Major Cities

The pandemic has shown us that broadband is not equally accessible at affordable prices even in our major cities. It wasn’t a rural part of America that had those little girls do their homework in a fast-food parking lot (picture below) that caught media attention, it was in Salinas, California, with a population density of 6,490 people per square mile.

Photo was taken at a Taco Bell in Salinas, California (https://www.ktvu.com/news/photo-of-girls-using-taco-bell-wifi-becomes-symbol-of-digital-divide)

Those kids probably had some basic Internet access, but it was likely too expensive and too slow to handle remote education. And that should come as no surprise given that a recent comprehensive study by the Open Technology Institute has found that the United States has on average the most expensive slowest Internet among modern economies

The lack of ubiquitous fiber infrastructure limits the government’s ability to support efforts to deliver access to those of limited income. When you don’t have fiber in those neighborhoods, all you can do is what the city of Salinas did, which was pay for an expensive, slow mobile hotspot. Meanwhile, Chattanooga is able to give 100/100 mbps broadband access to all of its low-income families for free for 10 years for around $8 million. Since the fiber is already built and connected throughout the city, and because it is very cheap to add people to the fiber network once built, it only cost the city an average of $2-$3 per month per child to give 28,000 kids free fast Internet at cost (that is, without making a profit). If we want to make free fast Internet a reality, we need the infrastructure that can keep costs sufficiently low to realistically deliver.

The massive discrepancy between fiber and non-fiber is due to the fact that the older networks are getting more expensive to run and can’t cheaply add a bunch of new users for higher speed needs. No amount of subsidy will change the physical limitations of those networks on top of the fact that they are getting more expensive to maintain due to their obsolescence.

The future of all things wireless and wireline in broadband is running through fiber infrastructure. It is a universal medium that is unifying the 21st century Internet because it has the ability to scale up capacity far ahead of expected growth in demand in a cost-effective way. It has orders of magnitude greater potential and capacity than any other wireline or wireless medium that transmits data. Our technical analysis concluded that the 21st century Internet is one where all Americans are connected to fiber and are actively supporting efforts in DC to pass a universal fiber plan and well as efforts in states like California. But for major cities, the lack of ubiquitous fiber is not due to the lack of government spending, it is from the lack of regulatory enforcement of non-discrimination.