When the massive, bipartisan infrastructure package passed Congress, the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) was tasked with ensuring equal access to broadband services. That provision is called “Digital Discrimination” and it states, for the first time in federal law, that specifically broadband access cannot be built along the lines of race, income, and other protected classes unless an ISP has an economic or technical justification for the discrimination. In other words, it is now a matter of federal law that digital redlining is banned.

Major ISPs fought hard to remove this provision, mostly because they’ve engaged in discrimination based on income status for many years. It is why EFF and dozens of organizations have called for a ban on digital redlining of broadband access back in 2020. Study, after study, after study has shown the same result. Wealthy Americans are getting fiber optic connectivity pushed closer to their homes starting as far back as 2005 while low-income people have been forced to stay on legacy copper and coaxial cable connections built as far back as 30 years ago.

But despite the evidence, the law, and the command by Congress, it is still a possibility that equal access for all Americans will be denied if the Senate does not confirm the Biden Administration’s FCC nominee, Gigi Sohn, to the agency. That is because the current four commissioners on the FCC have deep ideological differences of opinion with two believing broadband should be a regulated service with the other two supporting the full deregulation of broadband providers that started under the Pai FCC. Ms. Sohn’s public commitments have made clear she would support regulating broadband as an essential service, which aligns with where most Americans are today with 80 percent of people believing broadband is as important to their lives as electricity and water. If you support the idea that broadband should be treated as importantly as water and electricity, you should call your two Senators now and ask them to vote yes on Ms. Sohn.

Tell the Senate to Fully Staff the FCC

How Carriers Have Engaged in Digital Discrimination

2005 was the start of the transition towards fiber optics in broadband access in the United States at the last mile, which meant very different things depending on the type of last mile connection a carrier deployed. But the pattern is always the same, namely that large ISPs target areas where they believe their investment will return fast profits on a very tight Wall Street driven timeline of three to five years. That meant favoring areas willing to pay a lot for broadband as opposed to areas where profits would be more modest. This is why the quality of broadband services deployed is so uneven in any given community.

For telephone companies like AT&T and Frontier, upgrading to 21st-century access meant completely replacing their older AT&T monopoly-era copper wires, which were already hitting their capacity limits with DSL broadband. Fully replacing the wire required a significant investment in each household, which is why fiber to the home from these companies is so limited in the United States. It isn’t because its unprofitable to deploy, but rather they are just focusing on deploying to people who will pay very high prices for broadband for very high profits. For the rest, they are left on the old copper DSL system that has long ago been paid off. To use car rentals as an analogy, it is like having everyone pay the renters fee but only the wealthy get the new cars while poorer Americans can only have the used cars on the lot that were already paid off.

For cable companies like Comcast and Spectrum, upgrading their lines meant replacing only a portion of their coaxial networks with fiber because the underlying system was more data robust as a television distribution system. As far back as 2007, cable companies noted they would only have to spend a fraction of what telephone companies would need to spend in order to upgrade because of this incremental approach advantage. As a result, discrimination by cable companies looks different but shows up when you notice how low-income people can only get Internet Essential-type packages of low-cost low quality while everyone else enjoys access to gigabit connections. That happens because much like their AT&T/Frontier Communications counterparts, they choose to push the fiber closer and closer to areas with the highest profits while not pushing fiber towards less profitable low-income areas. If that trend is allowed to continue, cable networks will eventually become fiber to the home for the wealthy and legacy coaxial for low-income neighborhoods.

What this means is we are seeing the creation of 1st class internet and 2nd class internet neighborhoods within the same community where wealthy Americans will get faster and cheaper offerings while low-income people will remain with increasingly more expensive and slower connections. It will also stifle the effectiveness of low-income support programs such as the Affordable Connectivity Program because the underlying infrastructure would be unable to deliver 21st-century ready access. The wires will dictate the future of price and quality.

States With High Poverty Rates Have the Most to Gain from the FCC Enforcing the New Digital Discrimination Law

What is widely underestimated by policymakers is the extent low-income residents are profitable to serve with 21st-century access. They know that their low-income residents are being neglected when they are given spotty mobile hotspots or forced to use fast-food parking lot WiFi during the pandemic, but do not appreciate the extent the new law they created under the bipartisan infrastructure package will eliminate this problem if it is fully enforced. That is because low-income people are profitable to serve in the long run as networks are paid off. Fiber will last anywhere between 30 to 70 years once laid, which gives a carrier a much longer window of flexibility to recover the investment if the law pushes that result. So states with high poverty rates such as West Virginia, Louisiana, and Mississippi for example would invite the most scrutiny under the new digital discrimination law and also the most opportunity to recapture revenues the major ISPs are withholding from upgrading and investing into their networks. That means companies like Comcast probably can’t spend $10 billion on stock buybacks and raise dividends for shareholders because more and more of that money will need to be invested back into upgrading low-income access lines to comply with the law.

Carriers before the law were allowed to segregate and segment communities into sections to allow for greater profits stemming from that discrimination. Every dollar spent on a high-income person meant high returns while every dollar not spent on people closer to poverty was a dollar pocketed. The digital discrimination law forbids that going forward because you can’t treat people differently with your upgrade plans based on their income status. If the FCC forces ISPs to upgrade their networks equally so long as its economically feasible, it will force a shift by carriers to aggregate their costs and aggregate their revenues.

Profitability would come from the entirety of a community, not just from its wealthiest residents. And most importantly, they will still be profitable because the cross subsidization of high-income and low-income residents covers the expenses in the long run. What will end under the law is the siphoning of money from low-income broadband users to finance the wealthy. But all of this will depend on the FCC’s ability to carry out the new law. So long as it remains deadlocked, it will remain irrelevant and unable to make good on the promise of equal access to the internet.

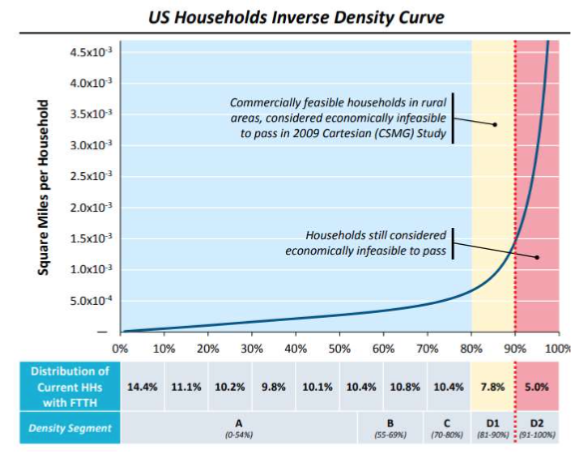

The FCC Will Be Responsible for Ensuring Equal Access for Nearly 90% of Broadband Connections Under the Digital Discrimination Law

The command by Congress is significant when it states only economic or technical justifications will excuse discriminatory deployment. That is because the commercial feasibility of deploying fiber upgrades according to one study already reaches 90 percent of American households with the costs rising rapidly for the final 10 percent (see chart below). For the final 10 percent where it is commercially infeasible to deploy, Congress gave $45 billion to the National Telecommunications Information Administration (NTIA) to provide to the states to issue grants under the infrastructure law. In other words, the FCC is responsible for the other 90 percent of American broadband users when it comes to ensuring equal treatment of investments and upgrades under the bipartisan infrastructure law.

Source: Fiber Broadband Association Cartesian study - Sep 10, 2019

But decades of neglect will take a lot of hard detailed work by the FCC for the agency to make good on the law’s promise. Just in the county of Los Angeles alone, which the University of Southern California found that black neighborhoods were being skipped for fiber upgrades, less than 50 percent of the county has upgraded 21st-century fiber broadband connections, which impacts nearly 5 million people. EFF’s own cost model study of LA County finds that 95 percent of LA County residents are economically feasible to fiber up before you even need a single dollar of subsidies. Just in that one region, the major ISPs are siphoning billions of dollars from underinvesting, despite it being profitable in the long run to upgrade nearly everyone today. Investigating, compelling ISPs to supply data to the government, and taking enforcement action when necessary to ensure compliance all will require a fully staffed FCC committed to enforcing the law. The major ISPs have nothing to fear from a deadlocked FCC, which is why they are investing so much dark money in preventing the confirmation of a 5th commissioner seat.