What started with a simple public records request became a journey into the absurd depths of Mexican bureaucracy. But we emerged victorious, and learned a lot about how a city experimented with a dangerous surveillance tool.

Filing public records requests for government information is a vital tool that EFF uses to shed light on law enforcement use of surveillance technologies. When a government agency hides crucial information about their surveillance policies and practices, it harms the democratic rights of the people whose data is collected and exploited.

In the United States, we rely on the Freedom of Information Act and state-level open government laws to obtain records from government agencies, but many other countries also have similar public records laws—including Mexico.

Mexican and U.S. authorities frequently collaborate and share resources, and surveillance techniques deployed by law enforcement on one side of the border often flow across to the other. In 2021, we investigated this flow of technology starting with a predictive policing program that we learned that police had launched in General Escobedo, a city in the border state of Nuevo Leon.

Predicción Delictiva–Predictive Policing, Mexican-style

Predictive policing refers to using algorithms and sometimes artificial intelligence to predict where crimes may occur or to identify who might commit them. These systems ingest a variety of data sources—such as surveillance data, crime reports, emergency calls, criminal records and social media—depending on which vendor is providing the technology.

This technology is flawed pseudo-science at best: the public safety equivalent of snake oil. Because the technology feeds off a biased and flawed data loop, it can result in pushing police toward communities that already are over-policed, such as communities of color, unhoused individuals, and immigrants.

We knew that General Escobedo, a municipality on the outskirts of Monterrey, had a predictive policing project because a government official publicly spoke about the program at a September 2018 meeting, according to records we found on the General Escobedo administration's website. According to the minutes of the meeting:

"En esa búsqueda de innovar para mejorar hemos incorporado una nueva herramienta a nuestro modelo policial consolidado, apreciado en el país y en el extranjero, predicción delictiva, PredPol. Que ha sido posible desarrollar porque somos el único municipio que tiene los registros estadísticos necesarios, sin esta información es imposible realizarlo, a partir de este próximo 12 de octubre con esta herramienta se nos permitirá predecir con altas probabilidades de acierto, donde se cometerá el próximo delito y por lo tanto evitarlo."

English translation:

"In this search to innovate, to improve, we have incorporated a new tool to our consolidated police model, which is valued in the country and abroad, crime prediction, PredPol. This has been possible to develop because we are the only municipality that has the necessary statistical records, and without this information it is impossible to do so, from this coming October 12 this tool will allow us to predict with high probability of accuracy where the next crime will be committed and therefore avoid it."

While the project was promoted as a technological miracle for public safety, we were determined to learn how it worked, how much it cost, who was providing the technology, and what problems it might cause. And to get that information, we needed to request records regarding the project’s development.

FOIA in Mexico

Mexico maintains a National Transparency Platform, through which people—including people who don't live in Mexico—can file public records requests. In October 2021, we submitted such a request to learn about how General Escobedo’s predictive policing system was implemented.

Before we delve into the absurdity, we need to be fair: The National Transparency Platform is a very useful tool. As an interface, it was easy to use and it efficiently facilitated a line of communication between the EFF team and the government officials responsible for ensuring information is released.

Filing the information request was probably the only simple part of this process. Then the problems began. Even if the software system is slick, transparency depends on the people who respond on the other end and how enthusiastic they are to fulfill your records request.

The first answer we received from officials in Escobedo was disheartening: Inexistencia de Información. The records didn't exist—or so they claimed.

We didn't believe this for a minute: How could a program receive an October 12, 2018 launch date without a long paper trail leading up to it? Like in many countries, the laws and rules at the national and state levels in Mexico require government-related institutions or those receiving public funds to keep records of any undertaken activities within their powers, including contracts and agreements, budget expenditure, approved programs, funding, and working plans.

But the flat denial of records wasn't even the most absurd part.

To try to prove they had done due diligence and met the requirements of Mexican public record laws, local officials sent us a photo essay of their "exhaustive search" ("búsqueda exhaustiva") for the records. For example:

Here they are outside the Secretaría de Seguridad Ciudadana building, where the records might be kept.

And now they're outside the door of the Dirección de Análisis e Investigación Policial (the directorate for police research and analysis).

Here they are searching for records on a computer.

And here they are looking in the drawer where they keep their mugs and coffee.

We had to look twice at that image: Were they really looking in the snack drawer for our documents?

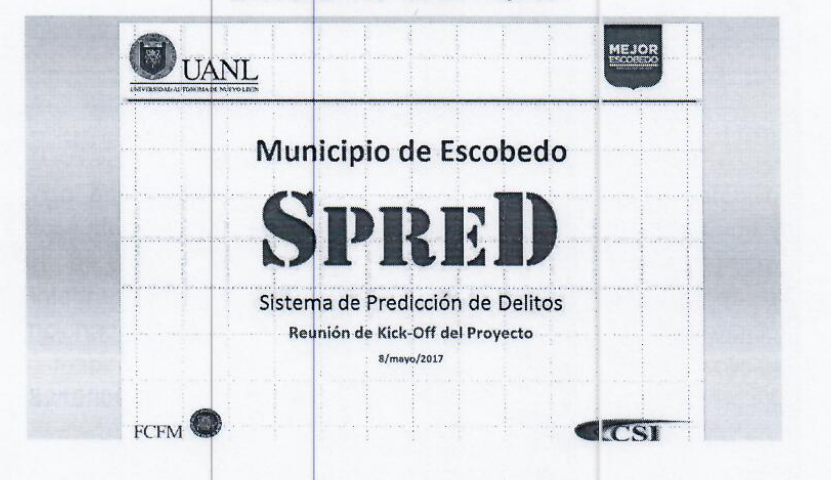

We went carefully through the photos, and we noticed that they did include screengrabs of documents that would've been responsive to our request: the first page of a slide presentation from the project kick-off and the cover of a user's manual relating to the predictive policing project, named Sistema de Predicción de Delitos (SPRED).

It made no sense: they showed us screengrabs of documents and then claimed that they didn't exist. Were they gaslighting us?

So We Appealed

We appealed to what was then called Nuevo León's Comisión de Transparencia y Acceso a la Información (COTAI - in English, the Commission for Transparency and Access to Information). Recently, it was renamed Instituto Estatal de Transparencia, Acceso a la Información y Protección de Datos Personales (INFONL- in English, the State Institute for Transparency, Access to Information, and Data Protection). This is the state's agency charged with ensuring access to information and adjudicating such appeals.

COTAI held two hearings on our request via Zoom. Both hearings were closed to the public, and only the person whose name was on the original request was allowed to attend on behalf of EFF.

No representatives from General Escobedo bothered to attend the first hearing, which frustrated both EFF and COTAI. When they attended the second hearing, municipal staff laid out their position: The SPRED program belonged to the previous administration and the current one decided to discontinue the project. Therefore, they did not have further information about the program, they claimed; they also claimed that the slide presentation and manual found in the search were only drafts, and therefore did not need to be released under law.

We insisted on getting access, and asked for a document showing that the project had been dropped.

By General and State law (art. 18 e 19) , state agents must document any act deriving from their powers or functions. As a result, the law presumes that such information exists, and, if not, the Transparency Commission may order state agents to produce the respective document (art. 43 (III), General law; art. 57 (III), State law). So if the municipal administration decides to discontinue a project described in a government action plan with public funds assigned, there must be documentation of that decision.

We explained our reasoning to COTAI, which agreed with us and ordered the city of General Escobedo to conduct another search for any information they had about the project.

What We Learned

Following our successful appeal, General Escobedo finally provided us with documents showing that the project was a collaboration between the city and the Universidad Autónoma de Nuevo León (Autonomous University of Nuevo León). The documents included the SPRED kick-off presentation, agreements between Escobedo and the university, and a slew of invoices and payments.

According to the presentation, the goal of the project was "to develop a mathematical model for crime prediction, the management of reported crimes and the visualization on maps of historical data and predictions for the municipality of General Escobedo, Nuevo León." The presentation also included a map showing the flow of data, including crime reports and historical crime data.

According to the presentation, Escobedo's C5 center (Centro de Coordinación Integral, de Control, Comando, Comunicaciones y Cómputo del Estado)—a type of high-tech public safety facility—would provide data from emergency calls. Meanwhile, the city's public safety agencies would provide data from police patrols. The administrative department would further collect feedback from public safety personnel. In addition, the system would be basing its models on five years worth of historical crime data.

What the presentation did not cover is any of the risks or pitfalls of this kind of model, nor did it include any steps officials would take to mitigate the potential harms. For example, if the algorithm is trained using five years of crime data—but that crime data was based on biased policing practices—the software could be expected to exacerbate that bias. Training an algorithm with emergency calls can also create problems in terms of equity, since that data can also be biased: Some communities may be less likely to call police when they experience or witness crimes, due to past negative interactions with law enforcement or the fear that police may be corrupt.

The records did show that the program represented a huge waste of public money. According to the agreement, Escobedo committed to pay up $5,220,000 (pesos, and including taxes) to the university for the project, and the records include a number of invoices and receipts showing at least $4,000,000 (pesos) checks were issued.

However, Escobedo refused to provide the SPRED manual to us, claiming that it could not be released due to its status as copyrighted work. We've seen similar problems in the U.S., with police agencies exploiting copyright exceptions to thwart public access to records. There was also a technical annex to the agreement between Escobedo and the university that we wanted to see; Escobedo provided both the manual and the technical annex to COTAI for review, but we are still awaiting its release.

In Conclusion

On one hand, we were pleased that Mexico's access-to-information law allowed us to (eventually) review relevant information about the program. Despite the hurdles we faced, Mexican public records law does have important safeguards that enabled us to effectively appeal the original denial. And COTAI proved its value by exerting its authority in favor of transparency, though it also decided not to disclose some of the documents that it received and reviewed. We were further heartened by the fact that Mexico allowed us—as non-Mexico residents—to access public information.

On the other hand, we are concerned with how this government entity developed a surveillance program and then delayed for many months any public accountability and related spending. This unfortunately reflects a trend we see across Mexico and around the world.

We owe a debt of gratitude to Article 19 México y Centroamérica, for sharing their prior experience with Mexico's transparency laws, and helping us navigate the byzantine appeals process.