Egyptian journalist Wael Abbas holds a special distinction: Over the years, he’s experienced censorship at the hands of four of Silicon Valley’s top companies. Although more extreme, his story isn’t so different from that of the many individuals who, following a single misstep or mistake at the hands of a content moderator, find themselves unceremoniously removed from a social platform.

When YouTube was still fairly new, Abbas began posting videos depicting police brutality in his native Egypt to the platform. The award-winning journalist and anti-torture activist found utility in the global platform, which even then had massive reach. One of the videos he had posted even resulted in a rare conviction of police officers in Cairo. But in late 2007, he found that his account had been removed without warning. The reason? His content, often graphic in nature, had been receiving large numbers of complaints.

Rights activists rallied around Abbas and were able to convince YouTube to restore his account; his archive of videos were eventually restored. YouTube later adjusted its rules to be more permissive of violent content that is documentarian in nature. Around the same time, Abbas’ Yahoo! email account was shut down—and later restored—on accusations that he was spamming other users.

More recently, Abbas has faced off with Facebook over an erroneous content decision made by the company. In November 2017, Abbas was issued a 30-day suspension by Facebook for a post in which he named and accused an individual of running a scam and threatening other people. As a result of the suspension, Abbas was unable to post to Facebook or use Messenger or other platform tools. After we contacted the company the suspension was reversed and Abbas’s access restored.

In another, more recent instance, Abbas had an image removed from Facebook, and received only a vague notification stating:

You uploaded a photo that violates our Terms of Use, and this photo has been removed. Facebook does not allow photos that attack an individual or group, or that contain nudity, drug use, violence, or other violations of the Terms of Use. These policies are designed to ensure Facebook remains a safe, secure and trusted environment for all users, including the many children who use the site.

Although Facebook pointed to their policies, they did not identify to Abbas which of his photos had actually violated the Terms of Use, leaving him guessing as to what he’d done wrong. A Facebook spokesperson commented:

In most instances involving content removals, we send people a generic message to let them know that they've violated our Community Standards. We're in the process of trying to be more specific with our language so that people have a better understanding of why we've taken down their content and how can they avoid similar removals in the future.

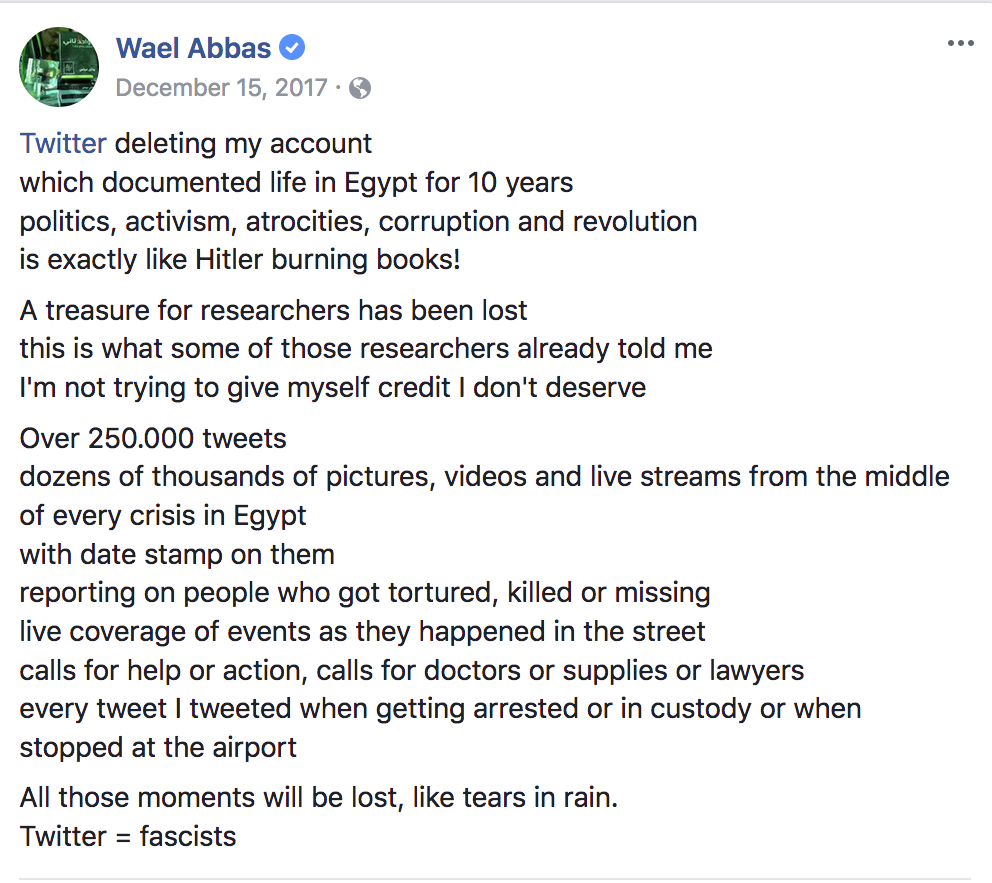

Wael Abbas writes about his Twitter account being suspended

Abbas was able to hold on to his Facebook account, but with Twitter, he wasn’t so lucky. In December, he was suddenly suspended from the platform without warning or notification. His account, which was verified and had 350,000 followers, was described by Egyptian human rights activist Sherif Azer as “a live archive to the events of the revolution and till today one of few accounts still documenting human rights abuses in Egypt.” EFF contacted Twitter about the suspension, but the company did not respond to our query.

Platforms must be accountable to their users

Social media companies took great pride in the role they were said to have played in the 2011 Arab uprisings. But as a recent article from Middle East Eye points out, Egyptians are facing a significant increase in content takedowns on Facebook. The article asks the question: “Would those social media accounts which supported Egypt's uprisings in 2011 now be shut down?”

In fact, the most famous of those social media accounts—the page entitled “We Are All Khaled Said” that first called for protests on January 25, 2011—was actually shut down by Facebook in 2010, just a few months before the uprising. The page, which was later revealed to have been created by Google executive Wael Ghonim, was removed because Ghonim had been using a fake name, and only restored after US-based NGOs stepped in to help.

Similarly, Abbas was only able to have his suspension overturned after contacting EFF. Verified Egyptian Reuters journalist Amina Ismail was able to get a Twitter suspension overturned through her contacts. Abbas and Ismail are both high-profile journalists, however—most users don’t have access to contacts at Silicon Valley’s top tech companies.

Wael Abbas's experience demonstrates the precarity of our online lives, and the dire need for platforms to institute transparent practices. As we recently wrote, social media platforms must notify users clearly when they violate a policy, and offer a clear path of recourse so that all users have an opportunity to appeal content decisions. Abbas's experience is the tip of the iceberg: for every prominent journalist documenting injustice who manages to get through their filters, how many more have lost the fight against the censors before they had a chance to reach a wider public?

It is vital that technology companies recognize the role they play in fostering free expression and act accordingly. To learn more about our efforts to hold companies accountable on freedom of expression, visit Onlinecensorship.org.