The San Diego regional planning agency, SANDAG, has been quietly rolling out a new mobile face recognition system that will sharply change how police conduct simple stops on Americans. The system, which allows officers to use mobile devices to collect face images out in the field, already has a database of 1.4 million images and serves nearly 25 federal, state and local law enforcement agencies in the region.

The San Diego regional planning agency, SANDAG, has been quietly rolling out a new mobile face recognition system that will sharply change how police conduct simple stops on Americans. The system, which allows officers to use mobile devices to collect face images out in the field, already has a database of 1.4 million images and serves nearly 25 federal, state and local law enforcement agencies in the region.

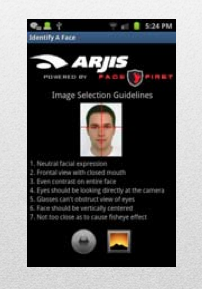

Over the summer, EFF sent a California Public Records Act request to SANDAG for more information on the program. From the records we received, we’ve learned that the program, called “TACIDS” (Tactical Identification System), serves law enforcement agencies as diverse as the San Diego Sheriff’s Department, the DEA, ICE, the California Highway Patrol and even the San Diego Unified School District. The officers use a Samsung tablet or Android mobile phone to take a picture of a person “in the field” and run that picture against databases of mugshot photos and DMV images from across several states to learn his or her identity. According to users, the system returns high-accuracy results in about eight seconds.

The Center for Investigative Reporting published an in-depth report on the program today, based in part on research conducted by EFF and the ACLU of San Diego and Imperial Counties.

The devices are supposed to be issued to “terrorism liaison” officers, but none of the documentation so far has shown any nexus between TACIDS use and terrorist activities. A chart we received (to the left) shows that, as of July 2013, there were 133 TACIDS-enabled mobile devices out in the field. While the San Diego County Sheriff’s Department had the most devices (55) and had made the most queries to the system (1,280), it was not the most proportionally active user. That honor went to the San Diego State University PD – the department only had one device (and presumably only one user of that device) but used it to make nearly 200 queries.

The devices are supposed to be issued to “terrorism liaison” officers, but none of the documentation so far has shown any nexus between TACIDS use and terrorist activities. A chart we received (to the left) shows that, as of July 2013, there were 133 TACIDS-enabled mobile devices out in the field. While the San Diego County Sheriff’s Department had the most devices (55) and had made the most queries to the system (1,280), it was not the most proportionally active user. That honor went to the San Diego State University PD – the department only had one device (and presumably only one user of that device) but used it to make nearly 200 queries.

CIR obtained more recent numbers that show the program has since expanded by another 45 devices, with a total of 5,629 queries since TACIDS launched. Even the California Department of Insurance and the Del Mar Park Rangers now have mobile facial-recognition devices.

One of the most concerning aspects of the system is that TACIDS allows officers to upload photos to its database right from the field. This means that officers can stop a person on the street, take her picture, and enter that picture in a biometric database based on little or no suspicion.

One anecdote in an official report from an Immigration and Customs Enforcement officer was particularly chilling:

“Today while conducting warrant services in Oceanside, we made contact with the neighbors of a subject we were looking for. As we were talking to the individuals who lived next door, our "spidy senses" were tingling. So this neighbor became the focus of a field interview. The subject was being evasive answering our questions. It was determined that the subject was in the United States illegally so we arrested him for that. I decided to transport the subject downtown, still not knowing exactly who I had in custody. While driving him to jail, I prodded a little more and the subject stated that in 2003 he received a conviction for DUI in San Diego and that was the ONLY time he was arrested. So I whipped out the Droid and snapped a quick photo and submitted for search. The subject looked inquisitively at me not knowing the truth was only 8 seconds away. I received a match of 99.96%. This revealed several prior arrests and convictions and provided me an FBI #. When I showed him his booking photo, his jaw dropped. Thanks again for the opportunity to evaluate this device.”

A TACIDS draft policy document shows that officers may collect face images in three distinct circumstances—each of which is problematic in its own right. First, officers may take photos of a person who “consents” to have his picture taken. The Supreme Court has said in several cases that if a person answers police questions when he should feel “free to leave,” the encounter is “consensual,” and it doesn’t trigger Fourth Amendment protection—even under circumstances where police conduct is such that no reasonable person would actually feel free to leave (such as when the cops block an exit or show their weapons). Based on laudatory comments about the TACIDS system like the one above, it appears officers are exploiting that perception to use TACIDS to identify people who aren’t under reasonable suspicion.

In the second scenario discussed in the draft policy, officers may collect a face image from anyone “lawfully detained.” In 2004, the Supreme Court upheld a Nevada law requiring people to identify themselves to police officers. The court held that as long as those stops were based on reasonable suspicion of criminal activity, they, too, did not trigger Fourth Amendment (or Fifth Amendment) protections. Stopping someone to take their picture to “identify” them would likely receive the same treatment under the Court’s analysis. However, as we’ve seen in the recent revelations about New York’s stop and frisk program, an overwhelming majority of these types of stops are not actually based on any objective reason to suspect a person of wrongdoing. And the NYPD’s own reports show that these programs overwhelmingly impact minority groups.

The third scenario contemplated by the policy is the most concerning. In that scenario, the cops are allowed to collect photos of people with whom they are not even in contact. This includes photos from security cameras and social media as well as “the capturing of facial images from a distance as part of surveillance operations.” As we discussed in our testimony to Congress on facial recognition last year, taking a person’s photo and entering it into a biometric database without her knowledge can have a serious chilling effect on First Amendment-protected activities. The Supreme Court has long recognized the societal value in the ability to remain anonymous and the ability to associate with others privately without fear that the government is watching. Using face recognition technology in the way proposed by SANDAG destroys this anonymity and puts everyone under the threat of government surveillance.

Although the draft policy includes some measures intended to protect privacy, these measures do not go far enough. For example, the policy explicitly allows face image collection based on First-Amendment protected activities like an “individual’s political, religious, or social views, associations or activities” as long as that collection is limited to “instances directly related to criminal conduct or activity.” But “criminal conduct or activity” is such a vague concept that it places no effective restrictions on police action. As we’ve seen in the ACLU of Northern California’s case challenging California’s DNA collection law, even peaceful political protests can result in arrest and biometric collection.

Not so long ago, our society would have recoiled from this type of stop and search. As an Arizona Supreme Court justice noted in 1983, “[t]he thought that an American can be compelled to 'show his papers' before exercising his right to walk the streets, drive the highways or board the trains is repugnant to American institutions and ideals.” In 1990, the Florida Supreme Court said police questioning based on no individualized suspicion was “foreign to any fair reading of the Constitution” and compared it to “Hitler's Berlin,” “ Stalin's Moscow,” and “white supremacist South Africa.” It’s disheartening to think how much has changed in the last 23 years and especially in the years since 9/11.

We hope that San Diego residents will push back on TACIDS before the program is rolled out to additional devices and agencies and linked to fixed video cameras in court buildings and on public transportation. We also hope that Americans across the country will question whether the impact of this type of technology on Constitutionally-protected activities is worth the huge cost and the minimal benefit to law enforcement from its use.

Documents:

- Department of Justice Letter Awarding $418,000 Grant for TACIDS Program

- Presentation on TACIDS Project to the National Institute of Justice

- 2013 SANDAG Presentation on the Progress of the TACIDS Program

- 2013 Presentation on SANDAG Technological Accomplishments, Including TACIDS

- 2013 ARJIS Report Regarding Contracts and the Urban Areas Security Initiative

- 2013 Final Report on TACIDS to the Department of Justice

- Joint Powers Agreement Between Regional Municipalities

- Privacy Impact Assessment Report for the Utilization of Facial Recognition Technologies to Identify Subjects in the Field

- FaceFirst Product Services Agreement

- San Diego Data Processing Corporation Contract With FaceFirst

- ARGIS Draft Policy for TACIDS

- San Diego Data Processing Corporation Contract with Airborne Biometrics

- Agency Allocations and Queries as of July 24, 2013

- Assignment of Contracts

- Automating Positive Identification in a Tactical Environment - Proposal to National Institute of Justice